Groucho Marx once said, “You’re headed for a nervous breakdown. Why don’t you pull yourself to pieces?” That, in fact, is what we’re going to do to our hero.

Now many writers focus on a Hero and a Villain as the primary characters in any story. And there’s nothing wrong with that. But as we are about to discover, there are so many more options for creative character construction.

Take the average hero. What qualities might we expect to find in the fellow? For one thing, the traditional hero is always the Protagonist. By that we mean he or she is the Prime Mover in the effort to achieve the story goal. This doesn’t presuppose the hero is a willing leader of that effort. For all we know he might accept that charge kicking and screaming. Nonetheless, once stuck in the situation, the hero drives the push to achieve the goal.

Another quality of a stereotypical hero is that he is also the Main Character. By this we mean that the hero is constructed so that the audience stands in his shoes. In other words, the audience identifies with the hero and sees the story as centering around him.

A third quality of the most usual hero configuration is being a “Good Guy.” Simply, he intends to do the right thing. Of course, he might be misguided or inept, but he wants to do good, and he does try.

And finally, let us note that heroes are usually the Central Character, meaning that he gets more “media real estate” (pages, screen time, lines of dialog) than any other character.

Listing these four qualities we get:

1. Protagonist.

2. Main Character.

3. Good Guy.

4. Central Character

Getting right to the point, the first two items in the list are structural in nature, while the last two are storytelling. Protagonist describes the character’s function from the Objective View described earlier. Main Character positions the audience in that particular character’s spot through the Main Character View. In contrast, being a Good Guy is a matter of personality, and Central Character is determined by the attention given to that character by the author’s storytelling.

You’ve probably noticed that we’ve used common terms such as Protagonist, Main Character, and Central Character in very specific ways. In actual practice, most authors bandy these terms about more or less interchangeably. There’s nothing wrong with that, but for structural purposes it’s not very precise. That’s why you’ll see Dramatica being something of a stickler in its use of terms and their definitions: it’s the only way to be clear.

At this juncture, you may be wondering why we even bother breaking down a hero into these pieces. What’s the value in it? The answer is that these pieces don’t necessarily have to go together in this stereotypical way.

For example, in the classic story of racial prejudice, To Kill a Mockingbird, the Protagonist function and the Main Character View are separated into two different characters.

The Protagonist is Atticus, played by Gregory Peck in the movie version. Atticus is a principled Southern lawyer in the 1930s who is assigned to defend a black man wrongly accused of raping a white girl. His goal is to ensure justice is done, and he is the Prime Mover in this endeavor.

But we do not stand in Atticus’ shoes, however. Rather, the story is told through the eyes of Scout, his your daughter, who observers the workings of prejudice from a child’s innocence.

Why not make Atticus a typical hero who is also the Main Character? First, Atticus sticks by his principles regardless of the dangers and pressures brought to bear. If he had represented the audience position, the audience/reader would have felt quite self-righteous throughout the story’s journey.

But there is even more advantage to splitting these qualities between two characters. The audience identifies with Scout. And we share her fear of the local boogey man known as Boo Radley – a monstrous mockery of human form who forms the stuff of local terror stories. All the kids know about Boo, and though we never see him, we hear their tales of his horrible ways.

At the end of the story, it turns out that Boo is just a gentle giant, a normal man with a kind heart but low intellect. As was the custom in that age, his parents kept him indoors, inside the basement of the house, leaving him pale and scary-looking due to the lack of sunlight. But Boo ventures out at night, leading to the false but horrible stories about him when he is occasionally sighted.

As it happens, Scout’s life is threatened by the father of the girl who was ostensibly raped in an attempt to get back at Atticus. Lo and behold, it is Boo who comes to her rescue. In fact, he has always been working behind the scenes to protect the children and is not at all the horrible monster they all presupposed.

In a moment of revelation, we, the audience, come to realize we have been cleverly manipulated by the author to share Scout’s initial prejudice against Boo. Rather than feeling self-righteous by identifying with Atticus, we have been led to realize that we are just as capable of prejudice as the obviously misguided adults we have been observing.

The message of the story is that prejudice does not have to come from meanness, but will happen within the heart of anyone who passes judgment based on hearsay rather than direct knowledge. This statement could never have been successfully made if the elements of the typical hero had all been placed in Atticus.

So, the message of our little story here is that there is nothing wrong with writing about heroes and villains, but it is limiting. By separating the components of the hero into individual qualities, we open our options to a far greater number of dramatic scenarios that are far less stereotypical.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Creating Characters from Scratch

Where Do Characters Come From?

When we speak of characters from a structural standpoint, there are very specific guidelines that determine what is a character and what is not. But when we think of characters in every day life, they are simply anything that has a personality, from your Great Aunt Bertha (though some might argue the point) to the car that never starts when you’re really late.

Looking back through time, it is easy to understand how early humans would assume that other humans like themselves would have similar feelings, thoughts, and drives. Even other species exhibit emotions and make decisions, as when one confronts a bear face to face and watches it decide whether to take you on or find easier pickings (a personal experience from my recent hike on the John Muir trail!)

But even the weather seems to have a personality by virtue of its capricious nature. That’s why they call the wind Mariah, why there is a god of Thunder, and why the Spanish say Hace Color, when it is hot, which literally means, “It makes heat.”

So while, structurally, to be a character an entity must intend to alter the course of events, in the realm of storytelling a character is anything that possesses human emotions. In short, structural characters must have heads, storytelling characters must have hearts. When you put the two together you have entities who involve themselves in the plot, and involve us in themselves.

Where Can We Get Some?

When writing a story, then, from whence can we get our characters? Well, for the moment lets assume we have no plot. In fact, we have no theme, no genre – we don’t even have any particular subject matter we want to talk about. Nothing. We have absolutely nothing and we want to create some characters out of “think” air.

Try starting with a name. Not a name like “Joe” or “Sally” but something that opens the door to further development like “Muttering Murdock” or “Susan the Stilt.” Often coming up with a nickname or even a derogatory name one child might call another is a great way to establish a character’s heart.

What can we say about Muttering Murdock? The best way to develop a character (or for that matter, any aspect of your story) is to start with loose thread and then ask questions. So, for ol’ Muttering Murdock, the name is the loose end just hanging out there for us to pull. We might ask, “Why does Murdock Mutter?” (That’s obvious, of course!) But what else might we ask? Is Murdock a human being? Is Murdock male or female? How old is Murdock? What attributes describe Murdock’s physical traits? How smart is Murdock? Does Murdock have any talents? What about hobbies, education, religious affiliation? And so on, and so on…. We don’t need to know the answers to these questions, we just have to ask them.

Why Does Murdock Mutter?

Next you want to shift modes. Take each question, one at a time, and think up all the different answers you can for each one. For example:

Why does Murdock Mutter?

1. Because he has a physical deformity for the lips.

2. Because he talks to himself, lost in his own world due to the untimely death of his parents, right in front of his eyes.

3. Because he feels he can’t hold his own with anyone face to face, so he makes all his comments so low that no one can hear, giving him the last word in his own mind.

4. Because he is lost in thought about truly deep and complex issues, so he is merely talking to himself. No one ever knows that he is a genius because he never speaks clearly enough to be understood.

You get the idea. You just pull out all the stops and be creative. See, that’s the key. If you try to come up with a character from scratch, well good luck. But if you pick an arbitrary name, it can’t help but generate a number of questions. If you aren’t trying to come up with the one perfect answer to each question, you can let your Muse roam far and wide. Without constraints, you’ll be amazed at the odd variety of potential answers she brings back!

Aging Murdock

Let’s try another question from our Murdock list:

How old is Murdock?

1. 18

2. 5

3. 86

4. 37

That was easy, wasn’t it. But now, think of Murdock in your mind…. Picture Murdock as an 18 year old, a 5 year old, an 86 year old, and at 37. Changes the whole image, doesn’t it! You see, with a name like Muttering Murdock, we can’t help but come up with a mental image right off the bat. It’s like telling someone, “Whatever you do, don’t picture a pink elephant in your mind.” Very hard not to.

The mind is a creative instrument just waiting to be played. It has to be to survive. The world is a jumble of objects, energies, and entities. Our minds must make sense of it all. And to do this, we quite automatically seek patterns. When a pattern is incomplete, we fill it in out of personal experience until we find a better match.

So, when you first heard the name, “Muttering Murdock,” you probably pictured someone who was in your mind already a certain gender, a certain age, and a certain race. You may have even seen Murdock’s face, or Murdock’s size, shape, hair color, or even imagined Murdock’s voice!

Give Murdock a Job!

Now ask one more question about Murdock – What is his or her vocation? Try out a number of alternatives: a school teacher, a mercenary, a priest, a cop, a sanitary engineer, a pre-school drop-out, a retired linesman. Every potential occupation again alters our mental image of Murdock and makes us feel just a little bit differently about that character.

Interesting thing, though. We haven’t even asked ourselves what kind of a person Murdock is. Is this character funny? Is he or she a practical joker? Does he or she socialize, or is the character a loner? Is Murdock quick to temper or long suffering? Forgiving, or carry a grudge? Thoughtful or a snap judge? Dogmatic or pragmatic? Pleasant or slimy of spirit?

Again, each question leads to a number of possible answers. By trying them in different combinations, we can create any number of interesting people with which to populate a story.

As we said at the beginning of the Murdock example, this is just one way to create characters if you don’t even have a story idea yet. But there are more! In our next lesson we’ll explore more of these methods.

Study Exercises: Reverse Engineering Characters

1. Pick a favorite book, movie, or stage play. Make a list of all the principal characters.

2. For each character, list all the key bits of information the author reveals about that character, as if you were writing a dossier.

3. Do a personality study of each character, as if you were a criminal profiler or a psychologist.

4. For each item you have noted in your dossier and profile, create a question that would have resulted in that item as an answer. In other words, play the TV game Jeopardy. Take an item you wrote about a character like, “Hagrid is a large man, so big he must be part giant.” Then, create a question to which that item would be an answer, for example, “What is this character’s physical size?”

5. Arrange all the questions you have reverse engineered in an organized list to be used in the Writing Exercises.

Writing Exercises: Creating Characters

1. Arbitrarily create a character name.

2. Use your list of questions from the Study exercises to ask information about this character.

3. Come up with at least three different answers for each of the questions.

4. Pick one answer for each question to create a character profile.

5. Read over the list and get a feel for your new character. Then, swap out some of the answers (character attributes) that you included in the profile for alternative answers you originally didn’t use.

6. Keep swapping out attributes until you arrive at a character you really have a feel for.

When we speak of characters from a structural standpoint, there are very specific guidelines that determine what is a character and what is not. But when we think of characters in every day life, they are simply anything that has a personality, from your Great Aunt Bertha (though some might argue the point) to the car that never starts when you’re really late.

Looking back through time, it is easy to understand how early humans would assume that other humans like themselves would have similar feelings, thoughts, and drives. Even other species exhibit emotions and make decisions, as when one confronts a bear face to face and watches it decide whether to take you on or find easier pickings (a personal experience from my recent hike on the John Muir trail!)

But even the weather seems to have a personality by virtue of its capricious nature. That’s why they call the wind Mariah, why there is a god of Thunder, and why the Spanish say Hace Color, when it is hot, which literally means, “It makes heat.”

So while, structurally, to be a character an entity must intend to alter the course of events, in the realm of storytelling a character is anything that possesses human emotions. In short, structural characters must have heads, storytelling characters must have hearts. When you put the two together you have entities who involve themselves in the plot, and involve us in themselves.

Where Can We Get Some?

When writing a story, then, from whence can we get our characters? Well, for the moment lets assume we have no plot. In fact, we have no theme, no genre – we don’t even have any particular subject matter we want to talk about. Nothing. We have absolutely nothing and we want to create some characters out of “think” air.

Try starting with a name. Not a name like “Joe” or “Sally” but something that opens the door to further development like “Muttering Murdock” or “Susan the Stilt.” Often coming up with a nickname or even a derogatory name one child might call another is a great way to establish a character’s heart.

What can we say about Muttering Murdock? The best way to develop a character (or for that matter, any aspect of your story) is to start with loose thread and then ask questions. So, for ol’ Muttering Murdock, the name is the loose end just hanging out there for us to pull. We might ask, “Why does Murdock Mutter?” (That’s obvious, of course!) But what else might we ask? Is Murdock a human being? Is Murdock male or female? How old is Murdock? What attributes describe Murdock’s physical traits? How smart is Murdock? Does Murdock have any talents? What about hobbies, education, religious affiliation? And so on, and so on…. We don’t need to know the answers to these questions, we just have to ask them.

Why Does Murdock Mutter?

Next you want to shift modes. Take each question, one at a time, and think up all the different answers you can for each one. For example:

Why does Murdock Mutter?

1. Because he has a physical deformity for the lips.

2. Because he talks to himself, lost in his own world due to the untimely death of his parents, right in front of his eyes.

3. Because he feels he can’t hold his own with anyone face to face, so he makes all his comments so low that no one can hear, giving him the last word in his own mind.

4. Because he is lost in thought about truly deep and complex issues, so he is merely talking to himself. No one ever knows that he is a genius because he never speaks clearly enough to be understood.

You get the idea. You just pull out all the stops and be creative. See, that’s the key. If you try to come up with a character from scratch, well good luck. But if you pick an arbitrary name, it can’t help but generate a number of questions. If you aren’t trying to come up with the one perfect answer to each question, you can let your Muse roam far and wide. Without constraints, you’ll be amazed at the odd variety of potential answers she brings back!

Aging Murdock

Let’s try another question from our Murdock list:

How old is Murdock?

1. 18

2. 5

3. 86

4. 37

That was easy, wasn’t it. But now, think of Murdock in your mind…. Picture Murdock as an 18 year old, a 5 year old, an 86 year old, and at 37. Changes the whole image, doesn’t it! You see, with a name like Muttering Murdock, we can’t help but come up with a mental image right off the bat. It’s like telling someone, “Whatever you do, don’t picture a pink elephant in your mind.” Very hard not to.

The mind is a creative instrument just waiting to be played. It has to be to survive. The world is a jumble of objects, energies, and entities. Our minds must make sense of it all. And to do this, we quite automatically seek patterns. When a pattern is incomplete, we fill it in out of personal experience until we find a better match.

So, when you first heard the name, “Muttering Murdock,” you probably pictured someone who was in your mind already a certain gender, a certain age, and a certain race. You may have even seen Murdock’s face, or Murdock’s size, shape, hair color, or even imagined Murdock’s voice!

Give Murdock a Job!

Now ask one more question about Murdock – What is his or her vocation? Try out a number of alternatives: a school teacher, a mercenary, a priest, a cop, a sanitary engineer, a pre-school drop-out, a retired linesman. Every potential occupation again alters our mental image of Murdock and makes us feel just a little bit differently about that character.

Interesting thing, though. We haven’t even asked ourselves what kind of a person Murdock is. Is this character funny? Is he or she a practical joker? Does he or she socialize, or is the character a loner? Is Murdock quick to temper or long suffering? Forgiving, or carry a grudge? Thoughtful or a snap judge? Dogmatic or pragmatic? Pleasant or slimy of spirit?

Again, each question leads to a number of possible answers. By trying them in different combinations, we can create any number of interesting people with which to populate a story.

As we said at the beginning of the Murdock example, this is just one way to create characters if you don’t even have a story idea yet. But there are more! In our next lesson we’ll explore more of these methods.

Study Exercises: Reverse Engineering Characters

1. Pick a favorite book, movie, or stage play. Make a list of all the principal characters.

2. For each character, list all the key bits of information the author reveals about that character, as if you were writing a dossier.

3. Do a personality study of each character, as if you were a criminal profiler or a psychologist.

4. For each item you have noted in your dossier and profile, create a question that would have resulted in that item as an answer. In other words, play the TV game Jeopardy. Take an item you wrote about a character like, “Hagrid is a large man, so big he must be part giant.” Then, create a question to which that item would be an answer, for example, “What is this character’s physical size?”

5. Arrange all the questions you have reverse engineered in an organized list to be used in the Writing Exercises.

Writing Exercises: Creating Characters

1. Arbitrarily create a character name.

2. Use your list of questions from the Study exercises to ask information about this character.

3. Come up with at least three different answers for each of the questions.

4. Pick one answer for each question to create a character profile.

5. Read over the list and get a feel for your new character. Then, swap out some of the answers (character attributes) that you included in the profile for alternative answers you originally didn’t use.

6. Keep swapping out attributes until you arrive at a character you really have a feel for.

Monday, October 29, 2012

A Method for Locating Personality Types in the General Population

Introduction:

Subject matter alone will not indicate personality type, as many different kinds of people are interested in the same things and have similar habits. Narrative psychology alone will not indicate personality type, as any two psychologically identical people may have complete diverse interests and habits. It is the combination of subject matter and underlying psychology that creates context.

This context provides identifiable fingerprints of specific personality types.

Method:

1. Determine the personality type you wish to be able to locate.

2. Find similar personality types in the historic record.

3. Do a storyform narrative analysis of each individual’s underlying psychology in each historic case.

4. Run comparisons among case studies for correlations between forensic subject matter and the underlying narrative psychology.

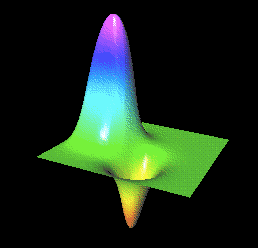

5. Create a cluster map showing the relative incidence of correlation of each individual story point in the analyses of historic cases of the same personality type.

6. From the correlation cluster, develop a probability template for each personality type to be used as a filter against the target population to identify matched individuals.

Subject matter alone will not indicate personality type, as many different kinds of people are interested in the same things and have similar habits. Narrative psychology alone will not indicate personality type, as any two psychologically identical people may have complete diverse interests and habits. It is the combination of subject matter and underlying psychology that creates context.

This context provides identifiable fingerprints of specific personality types.

Method:

1. Determine the personality type you wish to be able to locate.

2. Find similar personality types in the historic record.

3. Do a storyform narrative analysis of each individual’s underlying psychology in each historic case.

4. Run comparisons among case studies for correlations between forensic subject matter and the underlying narrative psychology.

5. Create a cluster map showing the relative incidence of correlation of each individual story point in the analyses of historic cases of the same personality type.

6. From the correlation cluster, develop a probability template for each personality type to be used as a filter against the target population to identify matched individuals.

Friday, October 26, 2012

The Coming Global Story Mind

As described in my previous article, Birth of a Story Mind, when people gather in groups, they self-organize into a group mind in which each individual specializes in one of our mental functions, such as becoming the voice of reason for the group, or the skeptic, or the conscience of the group. These functions are both cognitive and affective, and for the group mind to form, is must have all of those function at work within it.

In a large population of individuals, many group minds will naturally form as the anarchy begins to settle into organization. When group minds encounter one another as they move through the population, some will collide and shatter, some will maintain their identity but have their course altered by the encounter and focus on other subject matter, and some will combine to form larger group minds in which each smaller group begins to specialize to focus on one of our mental functions.

So, one group will come to express (or represent) the voice of reason within the larger group, while another will express skepticism, and still other will function as the larger group’s conscience. Just because a whole smaller group begins to focus or center on reason, as an example, does not mean that it stops having its own voice of reason with it, and its own skeptic and conscience. Rather, these individuals in the smaller group will still function as the voice of reason within the reason group, while another individual will still function as the skeptic in regard to reason.

In essence, one might say that as a small group specializes within a larger group, the members of the smaller group move with it, maintaining their relative positions within the small group as they all be come consistently biased toward the new thrust of their small group within the larger group. In other words, the individuals take on the flavor of their group as it evolves as a member group of a larger group mind.

This process is not unlike how solar systems form, gathering aggregate from dust to form small particles that combine into larger particles, rocks, boulders, and so on. It is also not unlike the way the brain works insofar as neurons in the brain (individuals) gather together into ganglia (little neural networks of a few thousand cells), which then gather into clusters and ultimately into the hemispheres of the overall brain

Like in a solar system, loose gas and dust gathers at the center of this evolving organization until the planets, story archetypes or social groups revolve around it. Eventually, this gravitational center reaches a critical mass and becomes a star, the Main Character for a story, or the identity of a social group.

When people feel they are members of a tribe, not just of their families, or of their state or nation, not just of their county or neighborhood, it is an primary indicator that one or more larger group minds above them has reached a critical mass and is burning with an energy from which they draw. In our own minds, this is our self awareness, the “I” in “I think, therefore I am.”

In the brain, the creation of such an identity requires a sufficient number of levels in the hierarchy – neural networks within neural networks, sub-minds and proto-minds within larger minds, following the same physical pattern as the story mind psychology, because the psychology is just a dynamic resonance of the underlying structural (physical) system that spawns and maintains it.

The cognitive functions are driven by the binary firing of the neurons. The affective functions are driven by the flow of neurotransmitters through the fluid-dynamic system of the brain. Note that neurons don’t just fire when stimulated. They fire with the electrical potential between the inside and outside of the neuron’s body (the axon) reaches an action potential of a certain differential.

This potential can be created by sufficient direct stimulation through spatial summation (multiple small stimulations all at once) or by temporal summation (a series of small stimulations that collectively increase the charge faster than the neuron can shed the excess through natural half-life style decay).

But this is just half the system – the binary network of neurons within larger networks, which are components within even larger networks. The other influence is the biochemical dynamic in which neurotransmitters affect the likelihood of firing.

Normally, neurons such as exciters and inhibitors are spewed out by one neuron’s boutons to be received by another neuron’s dedrites which pass the information to the axon which then may fire if it has received enough information either spatially or temporally.

But not all of these exciters and inhibitors actually make it from the boutons to the dendrites for they must cross a biochemical ocean – a small gap between the physical end of one neuron and the beginning of another. This gap is called a synapse and it holds one of the two keys to self awareness.

As some of these biochemicals drift out of the synapse into the general population of the brain at large, they form currents and eddies and standing waves of varying duration and complexity. These patterns also hold information, not of the binary cognitive kind, but of the analog affective kind.

When a wave forms at a particular synapse, it is may be more biased toward excitement or inhibition, depending upon its chemical make-up which is in turn determined by the collective impact of sensory stimulation of neurons which had previously fired.

These waves (really just concentration densities of chemicals) are also built from the shedding of potential from neurons that do not fire because they did not reach their action potential threshold.

Functionally, these concentrations can further moderate the effects of spatial and temporal summation so that a neuron which would ordinarily fire due solely to binary network stimulation by not fire because the surrounding biochemical environment lowers the action potential around the axon to the point it is inhibited below the threshold. Similarly, a neuron which normally would not fire, may do so anyway, because the biochemical environment about it increases the action potential beyond the threshold.

If the point of origin for network stimulation is observation, then the energy produced by the natural decay of neurons which don’t reach threshold is a parallel for internal thought. Along these lines, chemicals that act to excite can be analogized as our desires, and those that inhibit as our repulsions.

Now this is actually not directly true, for at the level of the whole mind / whole brain, desires and repulsions may be created by either exciting or inhibiting, thereby creating an inequity, which may be positive or negative to the mind at large in an affective sense. But I used those words to illustrate the fractal similarity of the lower brain function to the higher level psychology, in the first belief that while there are certainly many levels of similar organization in between, the end result is that the lower level functions are fractally layered until they influentially affect larger and larger systems, resulting ultimately in both our cognitive and affective attributes being organized in virtually the same pattern of relationships as the smallest components at the very bottom of the hierarchy.

Now, add this to the solar system model and the fractal psychology model of the organization of group minds and you can begin to get a sense how there is a parallel between a sun beginning to shine, a Main Character representing our own sense of self in a story mind structure, and groups forming and self-organizing into larger groups.

The general population that does not become part of a group is part of the gaseous material that collects in a growing gravitational sense of group identity until it ignites in a sense of self in which, like the biochemistry in the brain, the hierarchical functioning of organizations is moderated to be excited or inhibited by the general population in which they function.

And, as from the smallest interactions of neurons to the largest interactions of our thoughts and feelings, it requires many levels to build a truly functional mind to the point of self-awareness, such as national identity.

Communication among members of the general population is the key to their ability to act as an analog to the biochemical influence in the mind. Historically, increased communication outside the direct control of the organized neural networks (or socio-political groups) is an essential attribute to the freedom to form complex wave patterns (densities of opinions) which are sufficient to cause a group to act where it would not have by its own internal structure or to not act when it would have.

This is the nature of lobbyists, and of boycotts, and anti-boycotts in which the general unorganized components of society show their support or opposition to what the organization is planning or doing, just as the biochemistry affects the neurons and neural networks.

While communication had previously evolved to the point that many nations were able to achieve national identity, even today some nations have not yet coalesced into the level of self-awareness..

At an international level, everything from the formation of European Union to the Arab Spring illustrate the impact of internet and personal multi-media communication on the formation of identities for nations and even consortiums of nations.

But what of a global identity, a global group mind – the subject of this article? Clearly, the very same dynamics are at work among nations forming as group minds within a larger global mind – cognitively through channels (network hierarchy) and affectively through the global population (analog to the biochemical) by means of direct global communication among individuals of different nations.

Currently, this process is awaiting the advent of real time language translation that is accurate and effective to the fidelity of resolving idioms of one language into appropriate idioms in other so that the affective content in maintained.

When this happens, communication of analog, emotional information among individuals from all parts of the globe will become a functional dynamic wave-driven system, and with its advent a true global identity will reach critical mass and ignite into what amounts to a planet-encompassing self-wareness in which the earth itself may ponder, “I think, therefore I am.”

In a large population of individuals, many group minds will naturally form as the anarchy begins to settle into organization. When group minds encounter one another as they move through the population, some will collide and shatter, some will maintain their identity but have their course altered by the encounter and focus on other subject matter, and some will combine to form larger group minds in which each smaller group begins to specialize to focus on one of our mental functions.

So, one group will come to express (or represent) the voice of reason within the larger group, while another will express skepticism, and still other will function as the larger group’s conscience. Just because a whole smaller group begins to focus or center on reason, as an example, does not mean that it stops having its own voice of reason with it, and its own skeptic and conscience. Rather, these individuals in the smaller group will still function as the voice of reason within the reason group, while another individual will still function as the skeptic in regard to reason.

In essence, one might say that as a small group specializes within a larger group, the members of the smaller group move with it, maintaining their relative positions within the small group as they all be come consistently biased toward the new thrust of their small group within the larger group. In other words, the individuals take on the flavor of their group as it evolves as a member group of a larger group mind.

This process is not unlike how solar systems form, gathering aggregate from dust to form small particles that combine into larger particles, rocks, boulders, and so on. It is also not unlike the way the brain works insofar as neurons in the brain (individuals) gather together into ganglia (little neural networks of a few thousand cells), which then gather into clusters and ultimately into the hemispheres of the overall brain

Like in a solar system, loose gas and dust gathers at the center of this evolving organization until the planets, story archetypes or social groups revolve around it. Eventually, this gravitational center reaches a critical mass and becomes a star, the Main Character for a story, or the identity of a social group.

When people feel they are members of a tribe, not just of their families, or of their state or nation, not just of their county or neighborhood, it is an primary indicator that one or more larger group minds above them has reached a critical mass and is burning with an energy from which they draw. In our own minds, this is our self awareness, the “I” in “I think, therefore I am.”

In the brain, the creation of such an identity requires a sufficient number of levels in the hierarchy – neural networks within neural networks, sub-minds and proto-minds within larger minds, following the same physical pattern as the story mind psychology, because the psychology is just a dynamic resonance of the underlying structural (physical) system that spawns and maintains it.

The cognitive functions are driven by the binary firing of the neurons. The affective functions are driven by the flow of neurotransmitters through the fluid-dynamic system of the brain. Note that neurons don’t just fire when stimulated. They fire with the electrical potential between the inside and outside of the neuron’s body (the axon) reaches an action potential of a certain differential.

This potential can be created by sufficient direct stimulation through spatial summation (multiple small stimulations all at once) or by temporal summation (a series of small stimulations that collectively increase the charge faster than the neuron can shed the excess through natural half-life style decay).

But this is just half the system – the binary network of neurons within larger networks, which are components within even larger networks. The other influence is the biochemical dynamic in which neurotransmitters affect the likelihood of firing.

Normally, neurons such as exciters and inhibitors are spewed out by one neuron’s boutons to be received by another neuron’s dedrites which pass the information to the axon which then may fire if it has received enough information either spatially or temporally.

But not all of these exciters and inhibitors actually make it from the boutons to the dendrites for they must cross a biochemical ocean – a small gap between the physical end of one neuron and the beginning of another. This gap is called a synapse and it holds one of the two keys to self awareness.

As some of these biochemicals drift out of the synapse into the general population of the brain at large, they form currents and eddies and standing waves of varying duration and complexity. These patterns also hold information, not of the binary cognitive kind, but of the analog affective kind.

When a wave forms at a particular synapse, it is may be more biased toward excitement or inhibition, depending upon its chemical make-up which is in turn determined by the collective impact of sensory stimulation of neurons which had previously fired.

These waves (really just concentration densities of chemicals) are also built from the shedding of potential from neurons that do not fire because they did not reach their action potential threshold.

Functionally, these concentrations can further moderate the effects of spatial and temporal summation so that a neuron which would ordinarily fire due solely to binary network stimulation by not fire because the surrounding biochemical environment lowers the action potential around the axon to the point it is inhibited below the threshold. Similarly, a neuron which normally would not fire, may do so anyway, because the biochemical environment about it increases the action potential beyond the threshold.

If the point of origin for network stimulation is observation, then the energy produced by the natural decay of neurons which don’t reach threshold is a parallel for internal thought. Along these lines, chemicals that act to excite can be analogized as our desires, and those that inhibit as our repulsions.

Now this is actually not directly true, for at the level of the whole mind / whole brain, desires and repulsions may be created by either exciting or inhibiting, thereby creating an inequity, which may be positive or negative to the mind at large in an affective sense. But I used those words to illustrate the fractal similarity of the lower brain function to the higher level psychology, in the first belief that while there are certainly many levels of similar organization in between, the end result is that the lower level functions are fractally layered until they influentially affect larger and larger systems, resulting ultimately in both our cognitive and affective attributes being organized in virtually the same pattern of relationships as the smallest components at the very bottom of the hierarchy.

Now, add this to the solar system model and the fractal psychology model of the organization of group minds and you can begin to get a sense how there is a parallel between a sun beginning to shine, a Main Character representing our own sense of self in a story mind structure, and groups forming and self-organizing into larger groups.

The general population that does not become part of a group is part of the gaseous material that collects in a growing gravitational sense of group identity until it ignites in a sense of self in which, like the biochemistry in the brain, the hierarchical functioning of organizations is moderated to be excited or inhibited by the general population in which they function.

And, as from the smallest interactions of neurons to the largest interactions of our thoughts and feelings, it requires many levels to build a truly functional mind to the point of self-awareness, such as national identity.

Communication among members of the general population is the key to their ability to act as an analog to the biochemical influence in the mind. Historically, increased communication outside the direct control of the organized neural networks (or socio-political groups) is an essential attribute to the freedom to form complex wave patterns (densities of opinions) which are sufficient to cause a group to act where it would not have by its own internal structure or to not act when it would have.

This is the nature of lobbyists, and of boycotts, and anti-boycotts in which the general unorganized components of society show their support or opposition to what the organization is planning or doing, just as the biochemistry affects the neurons and neural networks.

While communication had previously evolved to the point that many nations were able to achieve national identity, even today some nations have not yet coalesced into the level of self-awareness..

At an international level, everything from the formation of European Union to the Arab Spring illustrate the impact of internet and personal multi-media communication on the formation of identities for nations and even consortiums of nations.

But what of a global identity, a global group mind – the subject of this article? Clearly, the very same dynamics are at work among nations forming as group minds within a larger global mind – cognitively through channels (network hierarchy) and affectively through the global population (analog to the biochemical) by means of direct global communication among individuals of different nations.

Currently, this process is awaiting the advent of real time language translation that is accurate and effective to the fidelity of resolving idioms of one language into appropriate idioms in other so that the affective content in maintained.

When this happens, communication of analog, emotional information among individuals from all parts of the globe will become a functional dynamic wave-driven system, and with its advent a true global identity will reach critical mass and ignite into what amounts to a planet-encompassing self-wareness in which the earth itself may ponder, “I think, therefore I am.”

Thursday, October 25, 2012

Defining and Identifying Personality Types

Wouldn’t it be great if we could have a list or a chart of all the major personality types in the world and all of their sub-types and variations? And wouldn’t it be even greater if we had a means of finding specific personality types in the real world?

Why, we could make social networks even more fun and compatible. We could build communities. We could better organize our clubs, better target our political parties, better understand our neighbors. We could improve advertising, more fairly judge punishments in court, predict what our adversaries might do. In fact, we might even be able to find home-grown terrorist and mass killers before they strike.

Problem is, though there are many theories, classifications and tests for personality, while each sheds some light on the issue, few of them have much overlap. Even definitions of “personality” show why, though we all can feel what personality is, we have very little understanding of what it is.

From Wikipedia:

From Dictionary.com:

2. a person as an embodiment of a collection of qualities: He isa curious personality.

3. Psychology.

a. the sum total of the physical, mental, emotional, and social characteristics of an individual.

b. the organized pattern of behavioral characteristics of the individual.

4. the quality of being a person; existence as a self-conscious human being; personal identity.

5. the essential character of a person.

From a narrative perspective, I believe that the nebulous appearance of the nature of personality is due to what we call in Dramatica theory the “blending of story structure and storytelling.”

As I often describe it, every story has a mind of its own: its own psychology and its own personality. Its psychology is determined by the underlying dramatic structure and its personality is developed by the storytelling style.

Well, after all these years, I’d like to revise that a bit. A story’s psychology is determined by the underlying structure and dynamics. A story’s personality is developed by the subject matter and style. A story’s persona is the combination of it’s psychology and personality.

You’ll note here that I have added a few things and rearranged the hierarchy around as well. To begin with, I added the word “dynamics” to “structure” in defining a story’s psychology because structure only describes the arrangement of elements the drive a psychology, but dynamics describes the potentials, resistances, currents and powers that determine how those elements will rearrange in the course of psychological function.

In addition, I added “subject matter” to “style” for without something to talk about, it doesn’t really matter how you say it.

And finally, I added a whole new level that combines both psychology and personality into the story’s persona. What is “persona?” I intend it to mean the sum product of our (a story’s) nature (structure), nurture (dynamics), experience (subject matter), and learned behavior (style). In short, it is our interface with the world – in essence, our face to the world.

Here’s how other’s define “persona.”

From Wikipedia:

In psychology the persona is also the mask or appearance one presents to the world.

From Dictionary.com:

5. a person’s perceived or evident personality, as that of a well-known official, actor, or celebrity; personal image;public role.

So, in essence, the persona is our public personality, while our true personality lies within. But, persona is not devoid of any elements of true personality. Rather, it is a filter and a manufacturer, hiding some things, creating others, continually adjusting the interface to maintain the least possible conflict with the external world while simultaneously minimizing the resulting internal conflict created between true self and presentation.

Well isn’t that a paragraph worth reading twice, I ask you! (Yes it is, I tell you).

Suggested by all this is that existing methods of defining and anticipating personalities are insufficient and therefore inaccurate because, while they have the persona down pat, personality and psychology can only be inferred from observation of the interface and not by direct observation.

Now we’d basically be screwed if it weren’t for an extremely fortuitous aspect of Dramatica narrative theory – the concept of fractal psychology. It holds the key to directly observing a story’s (or a person’s) psychology. And once that and the persona are both known, the personality can be calculated as the differential between the two.

Bear with me now as I take us on a little journey into the workings of fractal psychology, which will eventually lead us to a means of discovering the true underlying personalities of people both as individuals and in groups of any size.

Fractal psychology is the notion that when we gather in groups for a common purpose or to address an issue of common concern, individuals begin to specialize psychologically in terms of their function within the group. One will emerge as the voice of reason while another will take a skeptical position, for example.

The value of this specialization is that it brings greater fidelity in exploring the issue than would be achieved by having all members of the group be general practitioners, each trying to look at the problem for all perspectives, including our examples of reason and skepticism.

In a nut shell, each of these specialties is a function we have available in our own minds. By specializing, an individual gains value and potentially power. And, the group gains greater insight and capacity. So, driven by the personal motivations and collective benefits, any group of sufficient size will eventually self-organize into what is, effectively, a functional analog for the operating system and methodology of a single human mind.

And this means, the inner workings of psychology are mirrored in the definable and predicable externally observable world of human social organizational interactions. Now isn’t that a concept worth savoring!

Obviously there are a virtually unlimited number of applications one might create if you could define that system and use it not only to understand the workings of social groups, but also of individuals as well by projecting the system back into the minds from whence it came.

Nice dream, but how do you actually discover and document the elements of this organizational system? And even more challenging, how about the dynamics that describe the forces at work in such a system? They are harder to see, and even more difficult to quantitatively define.

Tough task. Where should we begin? Well, fortunately, someone already had started the process. Who? Authors and storytellers, as unlikely as that seems. You see, the reason for fictions is to look at human relationships in the hope of finding some repetitive patterns from which we might draw truisms that we can apply in our own lives.

If human interactions were truly chaotic, this would be a hopeless endeavor. But, since humans self organize into predictable patterns, these can be documented, and in fact they have been.

Literally thousands of generations of storytellers, in their attempt to reflect the reality of the human condition gradually refined these organizational interactions into the conventions of narrative structure and dynamics that we know today. And they carried the process quite a way along – but not all they way.

Without the understanding that organized human systems represent or mirror the functioning of a single human mind (we all it a Story Mind), there was no framework upon which storytellers could hang their collection of human elements and drives. They lacked a unifying perspective that could congeal the components of their understanding into a cohesive functional and predictive model.

And that is where we came in. Armed with our Story Mind concept, we recognized that framework, and seeing what it was, were able to further refine it into the Dramatica theory of story.

Let’s pause for a moment to take stock. In documenting the human condition, generations of storytellers identified many of the consistent elements and forces that define the way people relate. Because people in groups specialize and eventually self-organize into a system functional identical to the psychology of a single human mind, we were able to refine narrative conventions into an accurate model of the mind itself, at the level of psychology, below the level of personality.

Fine. We have a model of the mind. Now what does this enable in terms of defining and identifying personality types? To answer that question, let’s first take a look at the limitations of current approaches and then lay out how the Dramatica Theory can transcend those barriers.

Recall, early on in this article, that I mentioned the triumvirate of psychology, personality, and persona? Fact is, no one can ever directly observe any of those three except the persona – the mask, or publicly presented face of an individual or group. Psychology and personality can only be inferred. But since persona almost always is intentionally or at least unintentionally misleading, any inferences made from it are generally fuzzy and inaccurate at best.

If it weren’t for fractal psychology, for the model of the Story Mind, there’d be no getting around this. Yet with this model, we are able (essentially) to subtract the Story Mind component from the persona, leaving the pure personality behind. In plain speak, if you know the mask, and filter out the psychology, what is left is personality.

Now because personality (which consists of subject matter and personal or group interest) is built on top of psychology, it all falls into those cubby holes defined by the psychology. And this means that personalities fall into types.

The key to understanding how this works is to recognize that we all have the same psychological components, both structural and dynamic, but how much emphasis we give each one, how often we use them, this is determined by the subject matter and our interest in it.

So, while psychology alone can tell you about an individual’s or group’s mind set, and personality alone can tell you about an individual’s or group’s interests, it is the combination of the two that defines the true kind of type we ought to be defining. In other words, any given mind set (Story Mind) is neither good nor bad until it is applied to a particular real world subject.

Conceptual example: Is it moral to steal? No, if you are simply greedy; yes, if you are trying to feed your starving baby by taking from a tyrant who is hoarding all the food. It all comes down to context. Again, one psychology is neither good nor bad, until it is contextualized by personality (subject matter in which it operates).

And so, if we want to identify who is going to bring a gun into a theater and kill dozens of movie-goers the visible persona mask will not tell us, no matter how much number-crunching statistical data or tracking of purchases we do. But if we combine the interest in particular subject matter with specific psychologies, we can, in fact, predict the dangerous personality.

Further, if we look back at the historic record of the kinds of personalities we wish to become aware of before they act, we can determine their Story Mind psychologies and independently determine their subject matter personalities, and then statistically determine which combinations of the two appear over and over again in those who eventually act.

My expectation is that such a study and analysis would produce several different combinations of psychology and personality matching, each of which would represent a different “type,” though in the end all of those types might end up acting in the same way.

In this manner, a variety of different templates could be applied to the general population of individuals or even of organized groups, to identify those which may ultimately cause problems for society as a whole.

Preventive vigilance or Minority Report? You decide.

Why, we could make social networks even more fun and compatible. We could build communities. We could better organize our clubs, better target our political parties, better understand our neighbors. We could improve advertising, more fairly judge punishments in court, predict what our adversaries might do. In fact, we might even be able to find home-grown terrorist and mass killers before they strike.

Problem is, though there are many theories, classifications and tests for personality, while each sheds some light on the issue, few of them have much overlap. Even definitions of “personality” show why, though we all can feel what personality is, we have very little understanding of what it is.

From Wikipedia:

Personality is the particular combination of emotional, attitudinal, and behavioral response patterns of an individual.

1. the visible aspect of one’s character as it impresses others:He has a pleasing personality.

2. a person as an embodiment of a collection of qualities: He isa curious personality.

3. Psychology.

a. the sum total of the physical, mental, emotional, and social characteristics of an individual.

b. the organized pattern of behavioral characteristics of the individual.

4. the quality of being a person; existence as a self-conscious human being; personal identity.

5. the essential character of a person.

As I often describe it, every story has a mind of its own: its own psychology and its own personality. Its psychology is determined by the underlying dramatic structure and its personality is developed by the storytelling style.

Well, after all these years, I’d like to revise that a bit. A story’s psychology is determined by the underlying structure and dynamics. A story’s personality is developed by the subject matter and style. A story’s persona is the combination of it’s psychology and personality.

You’ll note here that I have added a few things and rearranged the hierarchy around as well. To begin with, I added the word “dynamics” to “structure” in defining a story’s psychology because structure only describes the arrangement of elements the drive a psychology, but dynamics describes the potentials, resistances, currents and powers that determine how those elements will rearrange in the course of psychological function.

In addition, I added “subject matter” to “style” for without something to talk about, it doesn’t really matter how you say it.

And finally, I added a whole new level that combines both psychology and personality into the story’s persona. What is “persona?” I intend it to mean the sum product of our (a story’s) nature (structure), nurture (dynamics), experience (subject matter), and learned behavior (style). In short, it is our interface with the world – in essence, our face to the world.

Here’s how other’s define “persona.”

From Wikipedia:

A persona, in the word’s everyday usage, is a social role or a character played by an actor. The word is derived from Latin, where it originally referred to a theatrical mask.

From Dictionary.com:

4. (in the psychology of C. G. Jung) the mask or façade presented to satisfy the demands of the situation or the environment and not representing the inner personality of the individual; the public personality.

5. a person’s perceived or evident personality, as that of a well-known official, actor, or celebrity; personal image;public role.

Well isn’t that a paragraph worth reading twice, I ask you! (Yes it is, I tell you).

Suggested by all this is that existing methods of defining and anticipating personalities are insufficient and therefore inaccurate because, while they have the persona down pat, personality and psychology can only be inferred from observation of the interface and not by direct observation.

Now we’d basically be screwed if it weren’t for an extremely fortuitous aspect of Dramatica narrative theory – the concept of fractal psychology. It holds the key to directly observing a story’s (or a person’s) psychology. And once that and the persona are both known, the personality can be calculated as the differential between the two.

Bear with me now as I take us on a little journey into the workings of fractal psychology, which will eventually lead us to a means of discovering the true underlying personalities of people both as individuals and in groups of any size.

Fractal psychology is the notion that when we gather in groups for a common purpose or to address an issue of common concern, individuals begin to specialize psychologically in terms of their function within the group. One will emerge as the voice of reason while another will take a skeptical position, for example.

The value of this specialization is that it brings greater fidelity in exploring the issue than would be achieved by having all members of the group be general practitioners, each trying to look at the problem for all perspectives, including our examples of reason and skepticism.

In a nut shell, each of these specialties is a function we have available in our own minds. By specializing, an individual gains value and potentially power. And, the group gains greater insight and capacity. So, driven by the personal motivations and collective benefits, any group of sufficient size will eventually self-organize into what is, effectively, a functional analog for the operating system and methodology of a single human mind.

And this means, the inner workings of psychology are mirrored in the definable and predicable externally observable world of human social organizational interactions. Now isn’t that a concept worth savoring!

Obviously there are a virtually unlimited number of applications one might create if you could define that system and use it not only to understand the workings of social groups, but also of individuals as well by projecting the system back into the minds from whence it came.

Nice dream, but how do you actually discover and document the elements of this organizational system? And even more challenging, how about the dynamics that describe the forces at work in such a system? They are harder to see, and even more difficult to quantitatively define.

Tough task. Where should we begin? Well, fortunately, someone already had started the process. Who? Authors and storytellers, as unlikely as that seems. You see, the reason for fictions is to look at human relationships in the hope of finding some repetitive patterns from which we might draw truisms that we can apply in our own lives.

If human interactions were truly chaotic, this would be a hopeless endeavor. But, since humans self organize into predictable patterns, these can be documented, and in fact they have been.

Literally thousands of generations of storytellers, in their attempt to reflect the reality of the human condition gradually refined these organizational interactions into the conventions of narrative structure and dynamics that we know today. And they carried the process quite a way along – but not all they way.

Without the understanding that organized human systems represent or mirror the functioning of a single human mind (we all it a Story Mind), there was no framework upon which storytellers could hang their collection of human elements and drives. They lacked a unifying perspective that could congeal the components of their understanding into a cohesive functional and predictive model.

And that is where we came in. Armed with our Story Mind concept, we recognized that framework, and seeing what it was, were able to further refine it into the Dramatica theory of story.

Let’s pause for a moment to take stock. In documenting the human condition, generations of storytellers identified many of the consistent elements and forces that define the way people relate. Because people in groups specialize and eventually self-organize into a system functional identical to the psychology of a single human mind, we were able to refine narrative conventions into an accurate model of the mind itself, at the level of psychology, below the level of personality.

Fine. We have a model of the mind. Now what does this enable in terms of defining and identifying personality types? To answer that question, let’s first take a look at the limitations of current approaches and then lay out how the Dramatica Theory can transcend those barriers.

Recall, early on in this article, that I mentioned the triumvirate of psychology, personality, and persona? Fact is, no one can ever directly observe any of those three except the persona – the mask, or publicly presented face of an individual or group. Psychology and personality can only be inferred. But since persona almost always is intentionally or at least unintentionally misleading, any inferences made from it are generally fuzzy and inaccurate at best.

If it weren’t for fractal psychology, for the model of the Story Mind, there’d be no getting around this. Yet with this model, we are able (essentially) to subtract the Story Mind component from the persona, leaving the pure personality behind. In plain speak, if you know the mask, and filter out the psychology, what is left is personality.

Now because personality (which consists of subject matter and personal or group interest) is built on top of psychology, it all falls into those cubby holes defined by the psychology. And this means that personalities fall into types.

The key to understanding how this works is to recognize that we all have the same psychological components, both structural and dynamic, but how much emphasis we give each one, how often we use them, this is determined by the subject matter and our interest in it.

So, while psychology alone can tell you about an individual’s or group’s mind set, and personality alone can tell you about an individual’s or group’s interests, it is the combination of the two that defines the true kind of type we ought to be defining. In other words, any given mind set (Story Mind) is neither good nor bad until it is applied to a particular real world subject.

Conceptual example: Is it moral to steal? No, if you are simply greedy; yes, if you are trying to feed your starving baby by taking from a tyrant who is hoarding all the food. It all comes down to context. Again, one psychology is neither good nor bad, until it is contextualized by personality (subject matter in which it operates).

And so, if we want to identify who is going to bring a gun into a theater and kill dozens of movie-goers the visible persona mask will not tell us, no matter how much number-crunching statistical data or tracking of purchases we do. But if we combine the interest in particular subject matter with specific psychologies, we can, in fact, predict the dangerous personality.

Further, if we look back at the historic record of the kinds of personalities we wish to become aware of before they act, we can determine their Story Mind psychologies and independently determine their subject matter personalities, and then statistically determine which combinations of the two appear over and over again in those who eventually act.

My expectation is that such a study and analysis would produce several different combinations of psychology and personality matching, each of which would represent a different “type,” though in the end all of those types might end up acting in the same way.

In this manner, a variety of different templates could be applied to the general population of individuals or even of organized groups, to identify those which may ultimately cause problems for society as a whole.

Preventive vigilance or Minority Report? You decide.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Narrative Dynamics 6 – The Grand Unifying Theory of Everything

Okay, so this is where I go a little nutso. Yeah, I know… But I’m going to be crossing the line that will prevent anyone from every taking my theories seriously again. Because I can.

Here’s the scoop….

The Grand Unifying Theory of Everything is:

The degree to which something exists is variable, and we perceive this as time.

There. I said it. And I believe it with all my heart. But what the heck does it mean?

It is a recipe for converting space into time and vice versa. It provides a map of the interface that stands between structure and dynamics, mind and matter, order and chaos, existence and oblivion. It is Einstein’s equation coupled with the Story Mind. It is the understanding I have been seeking for more than half a century. It is the culmination of my life’s work.

Here we go….

Go back to the Greek philosophers. Is there the prefect form of a things already in our heads, like the shape of a table or the essence of a bed, and we seek to achieve it in the material world, or do we create function in the real world, by building tables and beds, and from this arrive at a conceptual form to enclose a variety of things with similar criteria? In an overused phrase does form precede function or vice versa? This is another structural/dynamic paradox, for it depends upon perception: one man’s table is another man’s bed.

As in my last article, “The Interface Solution,” both form and function depend upon context, where one places the line, what one considers inside or outside the group. In short, we draw a circle around a number of things or attributes of a concept and define all that is inside as being of that nature and all that is outside is not.

Is a bed a mattress, a board, the ground? Can a table be a bed? Can a bed be a table? Of course they can! It all depends (from one philosophy) on what you use it for, and (from the other) on what you intended it to be. Both are correct, but not at the same time from the same perspective.

And then there’s the matter of time. A table may be made of stone or plastic or wood. Take a wooden table. One it was a tree. Some day it will dissolve into its component elements. When, exactly does it stop being a table? When you can’t use it as one any more or when you can’t recognize it as one any more?

Nothing exists absolutely. It only exists to a certain degree. Similarly, nothing does not exist absolutely. It always has the potential to become more fully what it has the potential to be.

Hence, the first part of the Grand Unifying Theory, “The degree to which something exists is variable.”

Now, imagine for a moment that time does not exist at all. Rather, there is only an ongoing rearrangement of how firmly anything exists. Everything has the potential to become anything else or to stop being anything at all.

This smacks of quantum theory which has described quanta as “vibrating packets of probability.” But as we have seen in my last article, a packet would have to be a closed system and no system is ever truly closed. Nor is any system ever fully open. It is all a matter of how we choose to perceive it.

Change, then, from being to not being or vice versa, from falling within a set or outside of it, from being open or closed, is a matter of perception.

Hence, time is not required to exist in the external world. All that must be is change in the degree to which something exists, which is then interpreted as a pathway that spawns the notion of causality.

Which leads us to the second part of the Grand Unifying Theory, “and we perceive this as time.”

The inference is that there is no time without perception, just as there is no existence. But perception alone is not sufficient to account for existence, for we must have something to observe in order to contextualize it as this or that, before or after.

The ramifications of this contention are that all we can know is a combination of change and awareness. We do not exist without the universe and it does not exist without us.

The essence of all this is that it requires both universe and mind, in perpetual equilibrium, ever re-balancing through endless process and endless reconsideration.

Deal with it.

Melanie

Here’s the scoop….

The Grand Unifying Theory of Everything is:

The degree to which something exists is variable, and we perceive this as time.

There. I said it. And I believe it with all my heart. But what the heck does it mean?

It is a recipe for converting space into time and vice versa. It provides a map of the interface that stands between structure and dynamics, mind and matter, order and chaos, existence and oblivion. It is Einstein’s equation coupled with the Story Mind. It is the understanding I have been seeking for more than half a century. It is the culmination of my life’s work.

Here we go….

Go back to the Greek philosophers. Is there the prefect form of a things already in our heads, like the shape of a table or the essence of a bed, and we seek to achieve it in the material world, or do we create function in the real world, by building tables and beds, and from this arrive at a conceptual form to enclose a variety of things with similar criteria? In an overused phrase does form precede function or vice versa? This is another structural/dynamic paradox, for it depends upon perception: one man’s table is another man’s bed.

As in my last article, “The Interface Solution,” both form and function depend upon context, where one places the line, what one considers inside or outside the group. In short, we draw a circle around a number of things or attributes of a concept and define all that is inside as being of that nature and all that is outside is not.

Is a bed a mattress, a board, the ground? Can a table be a bed? Can a bed be a table? Of course they can! It all depends (from one philosophy) on what you use it for, and (from the other) on what you intended it to be. Both are correct, but not at the same time from the same perspective.

And then there’s the matter of time. A table may be made of stone or plastic or wood. Take a wooden table. One it was a tree. Some day it will dissolve into its component elements. When, exactly does it stop being a table? When you can’t use it as one any more or when you can’t recognize it as one any more?

Nothing exists absolutely. It only exists to a certain degree. Similarly, nothing does not exist absolutely. It always has the potential to become more fully what it has the potential to be.

Hence, the first part of the Grand Unifying Theory, “The degree to which something exists is variable.”

Now, imagine for a moment that time does not exist at all. Rather, there is only an ongoing rearrangement of how firmly anything exists. Everything has the potential to become anything else or to stop being anything at all.

This smacks of quantum theory which has described quanta as “vibrating packets of probability.” But as we have seen in my last article, a packet would have to be a closed system and no system is ever truly closed. Nor is any system ever fully open. It is all a matter of how we choose to perceive it.

Change, then, from being to not being or vice versa, from falling within a set or outside of it, from being open or closed, is a matter of perception.

Hence, time is not required to exist in the external world. All that must be is change in the degree to which something exists, which is then interpreted as a pathway that spawns the notion of causality.

Which leads us to the second part of the Grand Unifying Theory, “and we perceive this as time.”

The inference is that there is no time without perception, just as there is no existence. But perception alone is not sufficient to account for existence, for we must have something to observe in order to contextualize it as this or that, before or after.

The ramifications of this contention are that all we can know is a combination of change and awareness. We do not exist without the universe and it does not exist without us.

The essence of all this is that it requires both universe and mind, in perpetual equilibrium, ever re-balancing through endless process and endless reconsideration.

Deal with it.

Melanie

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

Narrative Dynamics 5 – The Interface Solution

Sometimes the solution to a problem comes from a most unexpected source. Often, there is no relationship between the subject matter of problem and solution, but rather a dynamic resemblance, an analogy of system or operation.

A case in point is when I solved the mystery of the erratic sequential patterns that were created when plotting the order in which acts and scenes progressed through the four items of the quad.

The problem was that while we had it right that all four dramatic items in each quad would show up by the end of a story, when we drew that order on the quad it made one of three patterns: a U or C shape, an N or Z shape, and a hairpin shape. And what was worse, the sequence could go in either direction along the pattern.

We struggled with this for weeks – trying all kinds of ways to predict which pattern and direction combination would show up and not making any progress at all.

And then, one weekend I took my daughter to L.A.’s Museum of Science and Technology where they had a display of line of twenty-one bar magnets in a row, end to end, each on a spindle on a board. By turning the first one at just the right speed, you could get it to turn the one next to it, and if you continued this process, with a little practice, you could get all twenty-one moving at the same time.

And then it hit me – the sequences in Dramatica shouldn’t be plotted on the fixed structure. Rather, the structure was actually mobile – the elements twisting and rotating in response to the tensions of the story. The pattern was actually linear, but when the quads all wound up like a Rubik’s Cube, that straight line was warped and distorted into the three patterns we had observed.